I wrote this short investigative piece for a documentary class on migrant work in the UAE in my first semester of college at NYU Abu Dhabi.

The United Arab Emirates presents itself as a unique case study of immigration in that it is the world’s most heavily immigrant-populated country. Migrants coming from India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and the Philippines constitute majority of the expatriate population. The UAE requires a large migrant population due to the scarcity of native Emiratis, with “foreigners [outnumbering] the local population by more than five to one” (Habboush). The UAE began developing at an accelerating pace with the discovery of oil in 1962. As the country moved away from small-scale exports, a workforce focused on service and labor became necessary for maintaining the country’s development. The UAE continues to utilize the kafala system to organize its migrant workers, especially those working in domestic services and construction. The system necessitates that an Emirati or other expatriate sponsor workers attempting to gain entry into the UAE. The kafala system faces much criticism as it allows the sponsor an exorbitant amount of power (Kane-Hartnett). For example, sponsors frequently withhold their workers’ passports to control them, and although this practice is illegal, it is not heavily regulated, leaving workers unprotected. This practice is especially dangerous for female domestic workers, many of which are Filipina, as they remain trapped in their employer’s home in a cycle of repeated abuse. When these women are abused sexually the “law…(1) deters women from filing complaints and (2) stops complainants in pursuing a case” (“Women Migrant Workers in the UAE”). Filipina workers constitute seventy to eighty percent of the Filipinos coming to Arab countries, making them a relevant demographic in the study of the Emirates’ migration trends (“Women Migrant Workers in the UAE”). However, the kafala system, along with strict laws surrounding citizenship, allow the UAE to accommodate its migrant population.

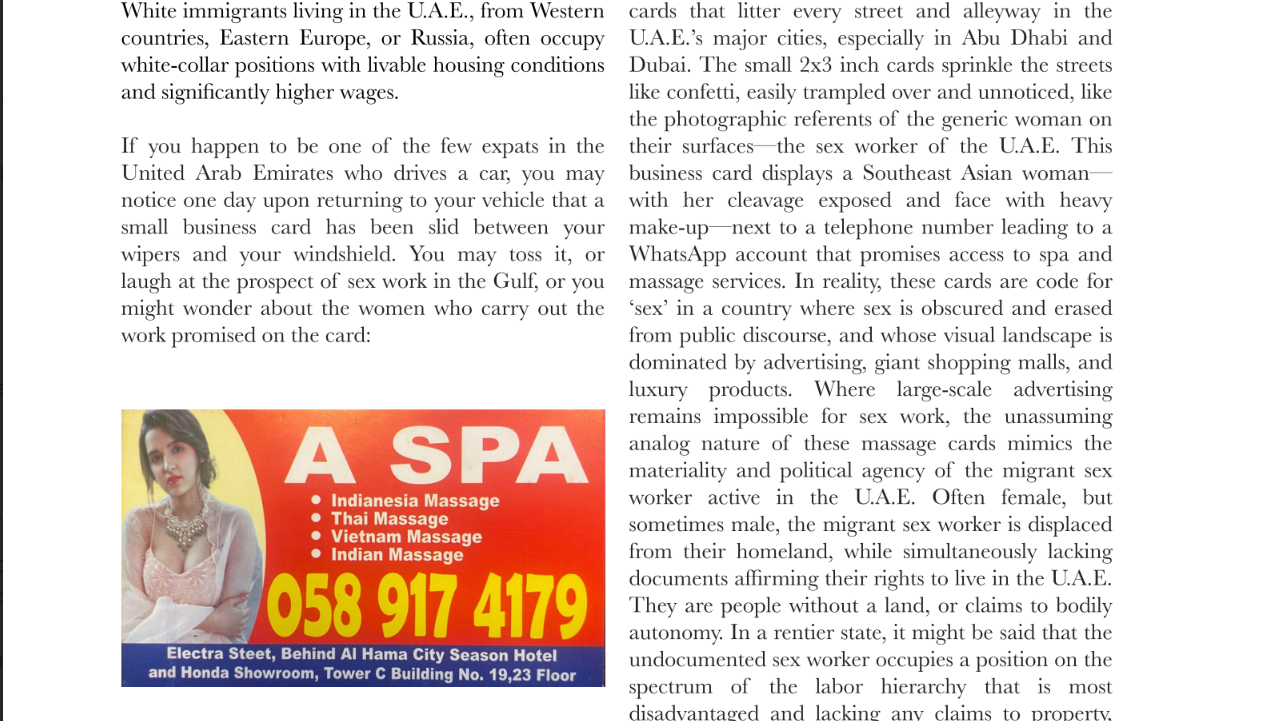

This project focuses on the Filipino migrant population in the UAE, which makes up 5.56% of the country (“United Arab Emirates Population Statistics 2018”), while exploring the experiences and areas that Filipinos make their own in the Emirates. The population I engage with remains largely unstudied, as Filipino immigrants in the UAE are called, “one of the most invisible groups and exploited groups” (Lucero). This population remains largely unstudied by anthropologists and majority of my sources are articles written about UAE or Gulf migrant workers as a whole. I did not seek out specific narratives in hopes of communicating the simple, everyday experiences of Filipino expatriates. Through interviews and photography, I uncover areas of cultural significance for Filipinos in the UAE. I believe I have addressed issues concerning religion, belonging, and family as immigration alters the meaning of each. For most of my interviewees, religion was a connection to their homes as it provided a place of belonging in a foreign country. Technology acted as a lifeline to their families as many of my subjects utilized WhatsApp and Facebook to communicate with loved ones back home. To communicate the variety of experiences related to the aforementioned topics, I combine interviews I conducted along with quotes from external readings. I provide a photo essay as a visual aid for the topics I introduce as problems or larger questions of immigration that have been addressed but require more research. I believe a mixture of factual and statistical information with anecdotal evidence will provide a small, but necessary outlook on the Filipino population in the UAE.

The UAE’s immigration system is known for its temporariness, as it requires migrants to frequently renew their visas. This renewal “depends solely on the employer” (Pardikar), creating a looming threat of deportation or jail time for expatriates. This temporariness increases the difficulty for Filipinos to find security in the UAE. Corruption clearly exists in the kafala system alongside an inescapable temporariness due to visa control. However, many Filipinos are gracious for the ability to work in the UAE, as they “are able to earn far more than they would otherwise have earned in their home countries” (Pardikar). This was apparent in all the interviews I conducted, with many of the subjects stating something along the lines of, “I came here in 2015 for a great opportunity. They offered me a good salary job so… I came here for a job.” For OFWs, the ability to make a better salary than they did in the Philippines is the driving force for coming to the Emirates despite the faults in the migration system and labor laws.

The UAE is famous for its lavish malls filled with high fashion brand names such as Chanel and Gucci, but for majority of the country’s migrants shopping malls aren’t an accessible place. This is explained in Yasser Elsheshtawy’s piece about Abu Dhabi’s city planning, “For them, shopping malls or the refurbished corniche are not viable meeting points since, given their status as low-income bachelors, they are viewed with suspicion” (103). Although this is discussing mainly South Asian migrants, it applies to low-skilled OFWs as well. To counter this stigma, Filipinos have opened ukay-ukay discount clothing shops. I have visited around five of these shops and mostly women work in them although I met one man who was proud to say he owned a storefront. The term “ukay” loosely translates to thrift shop in English, and these shops are where many Filipinos buy clothes in the UAE due to cost effectiveness. Clothing items never sell for more than twenty-five dirhams. Each shop has piles of clothes that one is meant to sit and sift through making this discount shopping a bonding activity, especially among Filipinas.

Abu Dhabi, and Hamdan Street specifically, is home to other discount stores that sell new items. These shops sell low quality clothes at cheap prices, and a variety of immigrants frequent these shops. I walked around a few of these shops and found that the most expensive items were shoes priced at forty dirhams. The legal alternative to this is outlet stores, such as the Adidas shop on Hamdan.

For Filipino immigrants, and immigrants in general, shops selling counterfeit items are an attractive alternative to malls. Karama, Dubai is known for this, and the UAE government has been cracking down on these shops. Immigrants still purchase fake items as they offer luxury items at a highly reduced price. A Filipina mother stated, “I do buy the Class A ones only if I am sure of the quality. The original ones are expensive. I can only shell out Dh100 for a bag. But if the quality is an issue, I wouldn’t waste even a Dh100 on it” in an interview Gulf News conducted. The alternative to paying 100 dirhams for a counterfeit bag is paying 15,000 dirhams or more in one of the UAE’s pricy malls. The shops in Karama, and elsewhere in the Emirates, show the divide in economic class between the UAE’s affluent and low-skilled migrant workers.

When discussing objects of migration various things come to mind such as nostalgic pieces, photographs, and family mementos. Additionally, food carries various cultural and social meanings that aid in the creation of safe spaces for migrant communities. Filipino restaurants in the UAE signify home for the vast number of migrants that come to work in Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

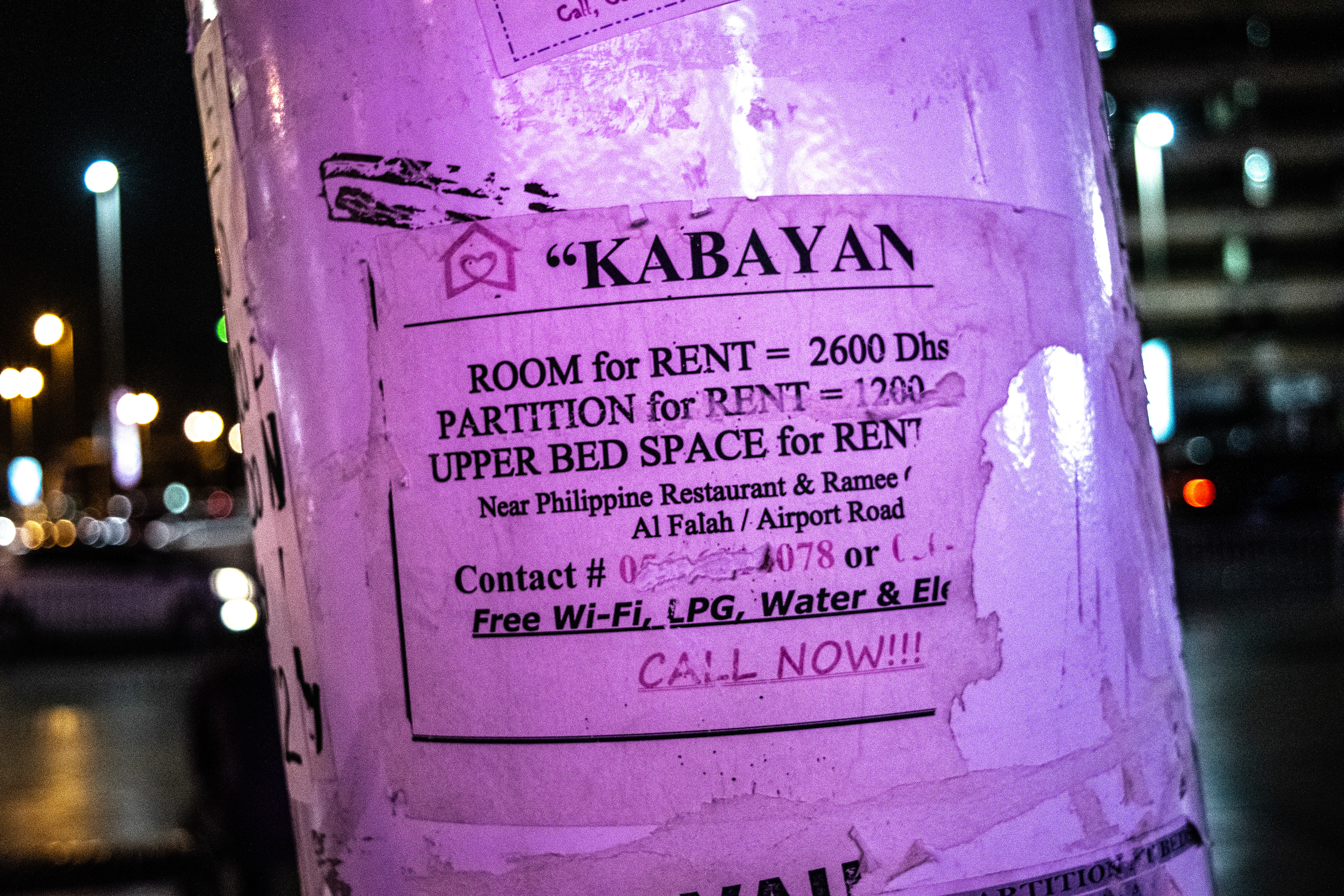

Panaderia is a Filipino bakery chain that opened in Abu Dhabi in 2008, and its mission statement reflects the idea of replicating Filipino culture in the Middle East: “It brings back happy memories of home away from home.” There are nineteen locations in Abu Dhabi and the bakers were happy to have their pictures taken in various locations on Hamdan Street and near Abu Dhabi Mall. Hamdan Street is home to various other Filipino restaurants that have popped up with an influx of Filipinos such as Philippine House Restaurant and the fancier Hot Palayok. Additionally, Kabayan Zone and Ortego’s Deli are located near Al Wahda Mall. Filipino restaurants in Abu Dhabi and Dubai are a symbol of financial success, and members of the Filipino community are active in supporting these businesses. The chairman of the Bayanihan Council stated in a talk given at NYU Abu Dhabi that he frequents these restaurants and uses Facebook to write positive reviews in the form of mini advertisements. With this, the communal aspect of Filipino culture is evident.

The UAE’s prominent supermarkets including Carrefour and LuLu Hypermarket feature Filipino snacks and deserts including ube cakes. In July 2018 LuLu Hypermarket had a festival showcasing Filipino foods that would be available in its locations in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Other miscellaneous hypermarkets scattered throughout Abu Dhabi offer entire Filipino food sections. Furthermore, SM Laguna Hypermarket opened in 2015 in Al Mariah Mall on Hamdan Street as the first Filipino grocery center in Abu Dhabi.

Although the UAE’s wealthiest malls are not accessible or affordable for majority of low-skilled migrant workers, it is easy to find many Filipinos working in Yas Mall, Al Wahda Mall, and the World Trade Center Mall. I spoke with an OFW in one of these malls who said: “I have been here for three months on a visiting visa. Luckily, I got hired here at this company.” This means highly respected companies are hiring undocumented migrants, as OFWs hired on visiting visas are illegal. This means they are not afforded the same protections under the law and can face jail time, making the process risky for both parties involved.

Religion, specifically Christianity, surfaced in almost all of my interviews. “More than 86 percent of the [Philippine’s] population is Roman Catholic” (Miller) and “9 percent [of the UAE] is Christian” (“United Arab Emirates” 2). Every Christian OFW I spoke with attends St. Joseph’s Catholic Church located near Umm Al Emarat Park in Abu Dhabi. The alternative for Catholic migrant workers is St. Mary’s in Dubai, the largest Catholic church outside of a Christian country (Pongratz-Lippitt). For many people I talked to, the UAE’s religious tolerance of Christians was an important aspect of their lives here. The chairman of the Bayanihan Council stated, “You can attend mass or church at any time you want to,” when discussing his sense of religious belonging in the Emirates. His coworker elaborated on this later in the discussion, “I have been to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Not to compare, but UAE is a much more open country than those two. It is a huge difference actually.” For many OFWs, religion comes into consideration when planning where they will work, and as discussed in The Actors, Christian Filipinos favor more Westernized countries due to their tolerance of Christianity.

Although the UAE is more religiously tolerant than other Muslim countries, there are still laws in place that prohibit “proselytizing and the public distribution of non-Islamic religious literature” (“United Arab Emirates” 1). These laws are often interpreted to mean that there should be no public display of Christianity such as Bible studies in public places. However, I have discovered that these activities take place in public parks and are well known in the community. Additionally, in an interview with an ukay-ukay shop owner I learned that there are various satellite churches in the UAE in cheaper malls (Al Mariah Mall) and KFCs. Curious about the legality of this, I emailed Reverend Andrew Thompson of St. Andrews Church. He stated:

“It is possible to get permissions to meet outside of a church compound from the ADTA board and a number of churches who meet in hotels, etc. have this written permission - in which case they are legal. If the churches do not have this permission, then they are illegal and that their activities are for now are being tolerated. However, if for any reason someone complains about the group (usually over noise pollution or parking issues), then they will be shut down in a heartbeat.”

Overall, churches provide a communal space for Filipinos to convene with other migrant workers and expatriate families in the UAE. An ukay-ukay shop owner explained, “Yes, I attend St. Joseph’s; we are Roman Catholic. There is a big community there …It is not mostly all Filipinos there, but it is mixed.” I attended a Friday service at St. Joseph’s and at least four hundred people were in attendance and had pulled up plastic lawn chairs up to the perimeter of the church’s parking lot. Majority of people were Indian or Filipino and many of them were children. Although the setting was religious, there were food tents set up for post-service meals that lead to people engaging in fellowship. Although the service was very diverse, some migrant workers opt for services in malls and fast food restaurants because the neighborhood the churches are situated in is very isolated. Reverend Andy elaborated on this, explaining that many laborers were bused to the churches and given the day off.

Migrant workers built the UAE. The chairman of the Bayanihan Council explained that someone close to the Sheikh said to him, “Filipinos in the UAE have been a constant part of the development of the UAE.” Although migrant workers are largely responsible for the country’s success, they are excluded from its main spaces. Despite this, small reminders of home have surfaced across the country. Observing these sites of interest lead to the discovery that Filipino culture has seeped into Abu Dhabi’s landscape in the form of churches and restaurants. In each space I discovered an aspect of Filipino culture despite the “oppression of daily life” (Elsheshtawy 94) that the planners of Abu Dhabi promote. These locations saturate the city, proving [Filipino] migrants create areas of belonging although they face segregation and an overbearing impermanence.